Chipped Blue Paint

Mi abuela came to America wearing a tattered potato sack, holding my mother, swaddled in palm leaves, in her good right hand, her only one left. With what little money she had, plus a few good games of poker, she bought a dingy, one-bedroom apartment in the basement floor of a crumbling complex in Hialeah, then declared from then on she’d only know success in life, whatever the cost. That was when the arsenic green wallpaper peeled off and the cockroaches fled through the near clogged drainage pipes and the rats darted out through the broken air vents and the front door. That was when my mother first cried after being silent since birth.

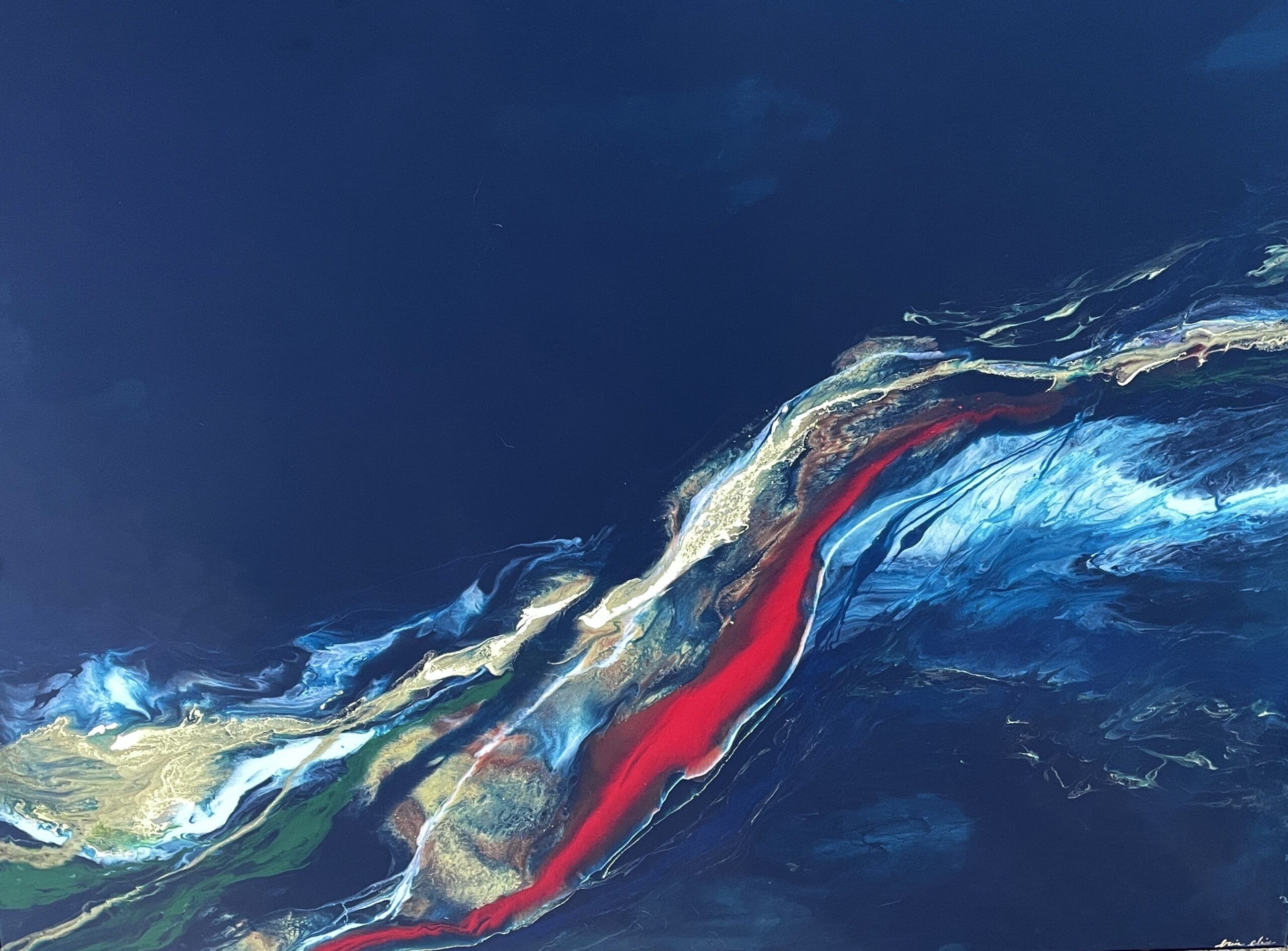

When I was born, Abuela repainted the walls sky blue, because it was a more regal color than brackish plaster. When I was born, my mother had barely entered high school, and my father had barely entered prison for preying on students. When I was born, I was named “Paris” because I reminded Abuela of her home city, the one she refused to remember and yet couldn’t forget. When I was born, I saw the color blue. To me it was the sky and the apartment was the world. The cracks in the wall were lighting, the faded paint the clouds, the leaky pipes the whistling rain that made me giggle while my abuela patched up the chipped paint.

My mother went to school in faux-mink coats. I went to school with knock-off Gucci bags when mink went out of fashion because of the mink abuse involved. Abuela decorated us like Christmas trees in fake diamond earrings and fake ruby necklaces and fake emerald rings, even though we always lost the fake jewelry that still cost her a pretty penny from the electricity bill. Abuela got us finishing school lessons so we’d have the same manners as the pretty rich girls at the good private Catholic schools my mother had always been pressured to get into through academic merit. Abuela somehow got me into one of those private Catholic schools despite raising me atheist.

When I was fourteen, I asked her if this was what success looked like.

“No,” she conceded. “But it’s close enough.”

For now, she added in Spanish under her breath.

“What does true success look like?”

Abuela sighed and flipped on the vintage TV set without color to The Real Housewives of Orange County, pointing out the opulent, tacky furniture and the women in Louis Vuitton heels.

“That. That’s what it looks like.”

My mother said that after she graduated community college she’d show her mother what real success looked like. Then she gained her Associates Degree in Nursing from Miami Dade, and passed the Boards Exam with minimal studying. Her first week on the job, she overworked three nights, and almost died of a heart attack, having to recover at home for three months, her left foot partially paralyzed, still allowing her to walk but with a noticeable limp like she had sandbags sewed to her leg.

“Is this what success looks like, Mama?” I asked her the morning after.

My mother glared for a minute, then weakly laughed. “Yes, mija. This is our pinnacle! Blue walls! Cracked ceilings! All we’re good for!”

My mother wanted to one day buy a pretty white house in Coral Gables, a lakefront property covered in palm trees and grand oaks and nearby good free public schools where cocaine wasn’t hastily hidden in ziplock bags stuffed down the boys’ urinal. My mother didn’t want to wake up another day to a decaying Victorian dresser, or an antique wicker rocking chair that looked chewed through by giant moths. My mother didn’t want fancy fake diamond jewelry. My mother didn’t want to wake up and see the same blue walls so faded, they seemed clinical.

Abuela said my mother was going around gaining success all wrong, that fortune required a sturdy foundation. In her homeland, a four-bedroom house wasn’t bought after growing out of a one-bedroom. Walls were torn down with hammers, recycled, rebuilt into new rooms, into new floors, new ceilings. A family home grows out of a tiny hut like a papaya tree grows from a single seed. A blight passed over the land—one of poverty and ill-lead revolution—which tore down long standing orchards full of sweet fruit. But here a new grove would grow. Here a new grove would thrive.

“Now hand me that roller,” she said after the lecture. “The wall paint is chipping off again.”

If success was blue wall paint, then success meant a new washing machine, a new radio, a new vanity mirror—all things my abuela bought with her own savings, also known as the electricity bill. So, on my first Black Friday in community college, I bought a flat screen TV with what money I’d saved scooping ice cream at a local Baskin Robbins by our apartment. My grandmother couldn’t hold in her joy when she saw it, hugging me in a near death grip and sobbing into my shirt.

“Now we can watch TV in color like our neighbors!” she exclaimed.

“It’s just a TV,” my mother said after getting home from her shift.

“It’s a flat screen!” Abuela argued.

“A flat screen means nothing if we can’t pay our electricity bill again this month.”

That night, Abuela abuela and I watched Desperate Housewives for the first time in color. That night, I saw in gold and silver the true wonder and splendor the reality stars lived in. That night, I saw clearly the cracks in the walls, heard and felt the leak from the pipes hitting the plastic bowls beneath them, saw in detail the fading or chipped blue paint. The next day, we sold the flat screen to pay the electric bill. We went without a TV set after that because we’d thrown out the vintage and couldn’t afford a new one.

And a few months later, she passed. And the day she died, I asked her if she missed Cuba.

“No,” she said. “You can’t miss what you’ve chosen to forget.”

“Why don’t you want to remember?” I asked.

The rocking chair she sat in creaked against the rotting wood floor. A single droplet of water landed on her nose, like a little glass piercing, clear and still as she slowly sat back in her seat until the rocking chair rocked no more. She seemingly looked through me, straight through as though I were a window pane, to the blue walls behind me, chipped and fading again, to be refurbished tomorrow. She sighed.

“We’re building a new life here, mija. To remember would be to love, and I want to love what we made here instead.”

“What did we make here?” I asked.

She passed before she would say.

After the funeral, my mother repainted the walls of the apartment white to make way for a “fresh start,” for true success apart from what came before. She sold the old furniture and fixed the pipes herself. Half the money that went toward paying my tuition at Miami Dade now went toward paying the electricity bill.

“It’ll be tight right now, but it’ll all be for the best in the end,” she said. “Once you graduate and pass your board exams, we’ll finally have the life we always wanted, the success we always dreamed of.”

I didn’t argue, didn’t make a peep in response. Instead I listened to the silence of the pipes, felt the lack of cracks on the not-so-thunderous walls. Instead I stared at the whiteness of our tiny, one-bedroom apartment. The cheap paint was either fading or chipping. I could still see the sky blue underneath.