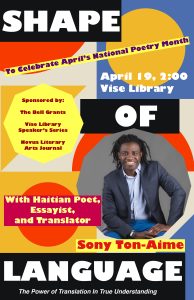

Sony Ton-Aime, Haitian Poet, Translator, and Essayist, Visits Novus Literary Arts Journal and Cumberland University for “The Shape of Language.”

Q and A with Sony Ton-Aime,

Director of Chautauqua Literary Arts…

Director of Chautauqua Literary Arts…

Novus: You recently visited Cumberland to meet and talk with the student body about the importance of translation in poetry and in better understanding other cultures as well as ourselves. Can you tell us a bit about how you got started in translation?

Ton-Aime: Thank you again for invitation and the chance to meet with the students. It was such a joy to witness their brilliance and creativity.

I have been translating since I was in elementary school. Now, don’t you think that was anything special because almost all my peers were doing the same. Growing up, most of our parents were illiterate. The few who could read did not have a strong grasp on French which was then the de facto official language. All the important documents were written in French. They still do, come to think of it. We, their children, were often asked to translate the documents our parents received. Can I add that to my résumé? Of course, not. But again, a résumé can only tell you so much.

Novus: Were you writing poetry from a young age? What about essays? Do you incline to identify more as a poet, essayist, or translator, or all three?

Ton-Aime: Oh yes, I started writing poetry at a very early. I have been fascinated with language since I was a child. You see, I was terribly shy. I did not speak much. I observed a lot. I would sit in a corner and watched people. The first time that I memorized a poem, I could not read. My brother was trying to memorize it aloud and I got it down before him. When I recited it for him, he could not believe it. After that, he would dare me to memorize other poems. I fell in love with the music and later with the wit of the poets.

Poetry became later my way of projecting the world that I was observing back to itself. Although, it would take years before I would let others read them.

I started writing essays later, way later. Not until my last year of high school, actually. I took a philosophy class and read Michel de Montaigne’s essays. His way of questioning everything, and especially his honest view of the self and our nature, struck a chord. I had, and still do, so many contradicting voices in my head, that I found the medium of the essay to be helpful. I do not need to be coherent in an essay. I can contradict myself. That’s liberating.

Novus: Do you identify most as a poet, essayist, or translator?

Tom-Aime: Well, lately, I have been thinking of myself as all three, but that was not the case a year ago. I used to think that I was just a poet because that was my MFA. However, I have come to accept that my poetry, or its essence, can barely be separated from my essays or my translation work. Especially, in the project that I am working on currently. Maybe, after I am done with it, I will return to being just a poet.

Novus: In translation, you are doing some innovative work. What examples can you provide in how you are translating specifically for Haitian readers?

Ton-Aime: Yes, I have been writing these pieces that I call “Haitian translations” for sometimes now. They originated out of my frustrated and complicated relationship with French culture. I both love and resent French culture. I grew up listening to French music and read French books. I am well aware that I only speak it because of colonization and resent the way that it has been used to separate me (the literate) from my parents and the others. It does not escape me that my ability to speak it is a mark of privilege, of othering. But I love it. I love its movements and its deliberateness. I love its history, its simple complexity, its contractions, its myriad of tenses and conjugations. And I love the writers writing in French from the Sahel to the Caribbean.

This is all to say that I could not stop reading and translating works written in French.

However, I felt very lonely, especially here in the United States. I felt far from my people. Every time I translated a work from the French to English, I felt it was only serving the French and the American audiences. My Haitian people were never present. But all the works the I was translating has some significance for Haiti or reminded me of it. I decided to start to add some “Haitian-ness” to my translations. For every work, I would have two translations; one that was a literal translation and another that kept the same poetic mechanism but told in the voice and context of a Haitian, mine. I have been having a lot of fun with them.

Novus: What most excites you about the translation process?

Ton-Aime: Oh, that’s a good one question. The work itself is exciting; creating something in collaboration with another person. It is not too different than reading, really. One is always in a constant state of surprise while translating. There is a mirror effect that happens between the two languages that is reminiscent of the synchronized movements of two expert dancers. Also, I am always so happy to witness the brilliance of the original author. It’s like a psychological experiment, digging deep into their creative process. It’s like you are in a laboratory and dissecting something. You got to be very careful, but at the end, you do find out how everything is put together.

Novus: How do you feel that translation can help us as readers to deepen our understanding of other cultures?

Ton-Aime: Besides the obvious fact that translation helps us sympathize with others by allowing us to learn about their stories, translation makes something clear for me. Language is both liberating and limiting. It is liberating because it is essential to our survival and creativity. Limiting, as it is a human creation, thus imperfect and incomplete. I am not talking only about the verbal aspect of language. Sign languages, with all their diversity and creativity, do the same.

One language can never be complete because it reflects only one group’s experiences and needs. For example, in places where it snows a lot, they might have many more words to describe snow than in a tropical place. And in that same example, the people living in temperate climate might come up with mechanisms to deal with the snow and create words for such things that would not be necessary in a tropical region. For a translator, these little discoveries are a treasure trove. It is a beautiful thing to witness up-close the creativity of the human species and to appreciate the subtle differences.

Novus: Has there been anything exciting or unexpected that you have learned about yourself or your own work via the translation process?

Ton-Aime: It’s more unexpected than exciting, really. Every time I am translating a piece, I am reminded of how much of my Haitian Creole I am losing. There are so many poetic and creative phrases that I used in Haiti that are gone from my vocabulary due to lack of use. I only remember them when I am working on a piece. It is both sad and exhilarating.

Novus: What translations should we be reading right now?

Ton-Aime: Open Letter Books is my reference when it comes to translations. The people there publish some of my favorite foreign authors, and their roster of translator is superb. They published my favorite contemporary French writer, Mathias Enard’s Zone and Street of Thieves. You should read him if you can. Start with Compass.

But the work in translation that I am most excited about now is Jean D’Amérique’s No Way in the Skin Without This Bloody Embrace translated by Conor Bracken from Ugly Duckling Press. Jean is currently my favorite Haitian’s writer.

Novus: Any upcoming or ongoing projects you’d like to mention?

Ton-Aime: Yes, thank you for the opportunity to plug! I was part of this exciting project put together by the folks at O’Miami. They brought writers from different countries in the Caribbean together for a translation project. They paired Caribbean descent writers born in the United States with those either living in or are from the Caribbean to translate each other’s works, and compiled them into a beautiful anthology, Off-Shore/On-Shore collection. https://omiami.org/shop/on-off-shore

Novus: This has been wonderful getting to know you, Sony, and to have you visit with our Editorial Staff, our Creative Writing Club, and the University Library Speakers’ Series as a Visiting Artist. We wish you all the best with your important and dynamic work.