Poetry

The Going

Had a line without a poem with a horse on fire.

Thought, I should write that down before it’s gone.

Worked the door last Halloween past afterhour,

reading Oliver Stone’s dour script for Conan

on my iPhone, thought about what goes unmade,

how there must be unbearable solitude in achievement.

Best not to speculate. Didn’t the Barbarian’s creator,

Robert Howard, die from self-inflicted wounds,

quoting lines from ‘House of Caesar’ in the West?

There must be a thousand big goons in a boomtown.

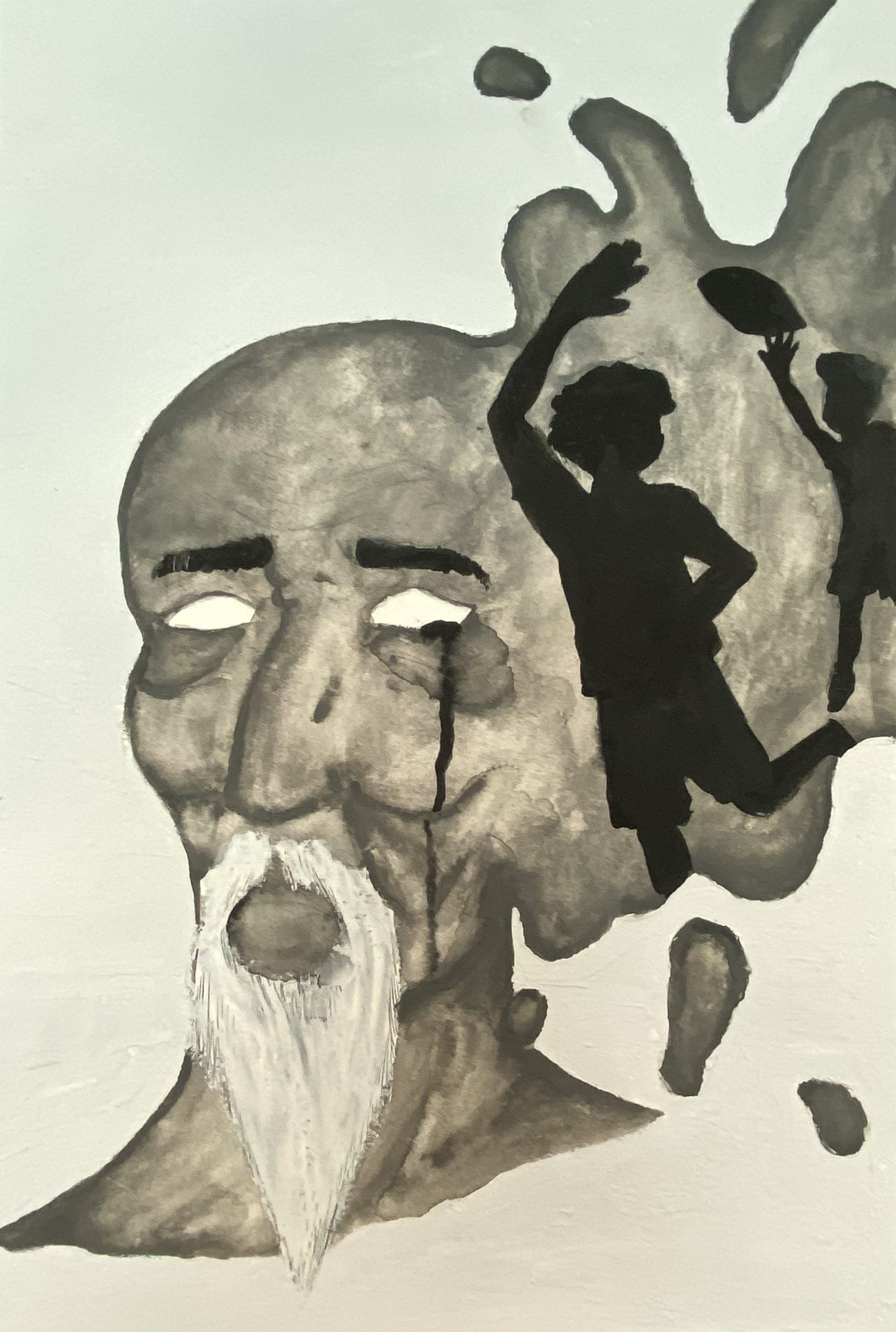

When a man thinks about the past he becomes kinder,

KINDER, Andrei Tarkovsky said. I suppose

it’s the look of compassion you see on stallions in public

monuments, the bowed chin, on bit, bones in

lingual tension, or behind the restrained pose horseface

Conan assumes in Frank Frazetta’s illustrations.

I practice it in flashes on the backbar’s mirrored glass –

something that can take a hit, my gait as, my heart as.

I fake I’m watching Eoghan cut gain onstage

or the Melbourne Cup on TVG. FanDuel.

I learned the horses doing nights a yearlong,

working the door unlatched, letting Denil in again

to mop gore from his face, giving him shit, my shirt,

as though brute strength’s its own costume.

You might say Conan was a product-of-his-world like

real punters talk about conditions of The Going –

the green turf goes you hard & heavy, good or good.

To firm -to soft, soft – pliant enough to fall through

to the underage of earth, stirring in its soaked

fur like some antediluvian beast. Man, though,

naked, big, and dull as I’d look in the Hyborian Age,

I could forecast a foal. I could make its book

a line without a poem like my life for hire.

Contingent Faculties

Midmorning abeam, abuzz, aubade about

walking our old block, applauding the view

that Yonkers is fair facsimile of my twenties. I can’t.

I can’t unthink pariah dogs queuing on rain’s garnet,

canines bared like tracer bullets at the street – nothing new

about collaborating with synecdoche of oneself.

The past. I could touch it almost, open

the day like a devotional book, work its clasp like

a dog’s flews and stare down its gullet, gasp

into living dark. Wycliffe called it

vtmer derknessis in St. Matthew’s account

of the healing at Capernaum (the desperate centurion

with his palsied son), translating Christ’s address as Parable of the Weeds.

Ther schal be wepying and gryntyng of teeth.

My mind works through this forecast of tears

and how it was ten years before I first came to New York

that I last took the bus from Echo Industrial Park,

believing it possible, then, to be reborn as morning

is, shedding night’s clothes at the close of shift.

Now I dog the blunting of an uncertain future

at midcareer. Health to the new bosses, sure.

As Christ sat at meat in Matthew’s house,

loud as a beaten dog, perhaps my namesake knew

the thousand ways to be shameless in a small town.

Perhaps knew that for small men, leaving leaves

nothing to choose between living & the life.

workworkworkworkworkworkworkworkworkw

orkworkworkworkworkworkworkworkwor

kworkworkworkBEASTworkworkworkwork

workworkworkMANworkworkworkwor

kworkworkworkworkworkworkworkwork

Asking Why on the White River

Asking why on the White River,

you tell me about the time you tried

to kill yourself, dropping to the side

of a California highway.

Later that night

I’m spitting tobacco juice down the drain,

remembering how I laid crucifix in the grass,

touched it with trembling hands in triumph

at the memory of a near six year drawl

prophesying over me: the grass

would never be greener.

Known only by the glow of cheap cigars

I tell you why I won’t sing hymns.

You tell me you were in love once.

I ask myself how to know what it feels like

and why time is a mechanism

of middle grade clarity.

The spin and ache of hours draws truth

from history, admissions staining the water

in incantations of suffering. Nicotine

behind my eyes, beneath my tongue

like a rudder as I say to the sky

I never wanted the grass.

I wanted what is now in front of me:

tall trees casting silhouettes on black water.

Neighbor

When the next-door neighbor

Molotov cocktailed our house

just after a midnight in June,

all four of us were asleep, we

who’d moved back home to the

Pacific Northwest after two

decades of lake effect snow,

thanks to those bodies of water

known as the greats. Their

delivery, similar to his, dropped

a cold so quick we’d often wake

like we did when the firemen

lumbered through our house

that hot night. Sometimes, the

Michigan snow kept closed

all that could open. Sometimes,

our next-door neighbor stood

out in the rain, his neck craning

at the possibility of drones above.

Snow can fool you, if you look

at it long enough. Everywhere

starts to look like it’s down.

If you don’t have an opening,

thoughts can take you there,

too. At the trial, our next-door

neighbor confessed to thinking

we were the bad neighbors from

years ago. I opened a door in the

place where I live. I asked him to

come inside.

Dumpster Balloons

As I opened the dumpster

to empty the week’s trash, birthday balloons rose

to greet me, as if bonded to the lid,

charged with anticipation.

I scrambled to shut them down

yet they kept rising, obedient to unseen forces

brazen they squirmed toward

the black open air.

How vast the continuum of emotions

permissible each moment on earth.

A Ukrainian couple proclaims their vowels

while dressed in army fatigues,

flower petals decend upon the same ground

pierced each night with metal-cased shells.

Shirtless boys giggle while dribbling a ball

across the dusty floor of refugee camps.

A celebration for being alive,

a witness to one more orbit,

even with the hurt, the bitterness,

the weight we carry.

Wilting Winters

I ponder on the idea of great fields,

Petals falling from yellow roses,

How their stems wither upon departure.

The winter mornings resist blooming,

Dandelions carried away until spring,

Frost creeps over their corpses.

Their memories live in the depths of summer,

November air fades the tint,

And no small hands

Reach for them to carry inside before dinner,

As mom cooks over the oven,

And dad comes home too late.

The grass of the fields never stops swaying, even

As the air begins to dim

And flowers bend.