Among the Storm

You build a home

among the torrents

I watch you in the deep end.

You were not born

in this storm – it hijacked

You and proliferated, raised

its children in Your lungs

to take the wind out.

A storm isn’t normally

the antithesis to wind.

A storm doesn’t normally

whitewash Tacoma, or the streets

leading from church to home

stalking Manuel Ellis

to take the wind out of his lungs.

A storm doesn’t normally

bring riots, though maybe storms should,

or maybe there shouldn’t have to be

a storm

for us to riot.

In this storm, hail cannons

down like rubber bullets

while forest fires

pepper spray the West.

A thrown water bottle

becomes a line of riot shields

charging into umbrella defenses.

The storm comes from all directions now and

my dog, my house, my street,

my 11th and Pine, my Seattle

does not sleep at night.

How can this be place for home?

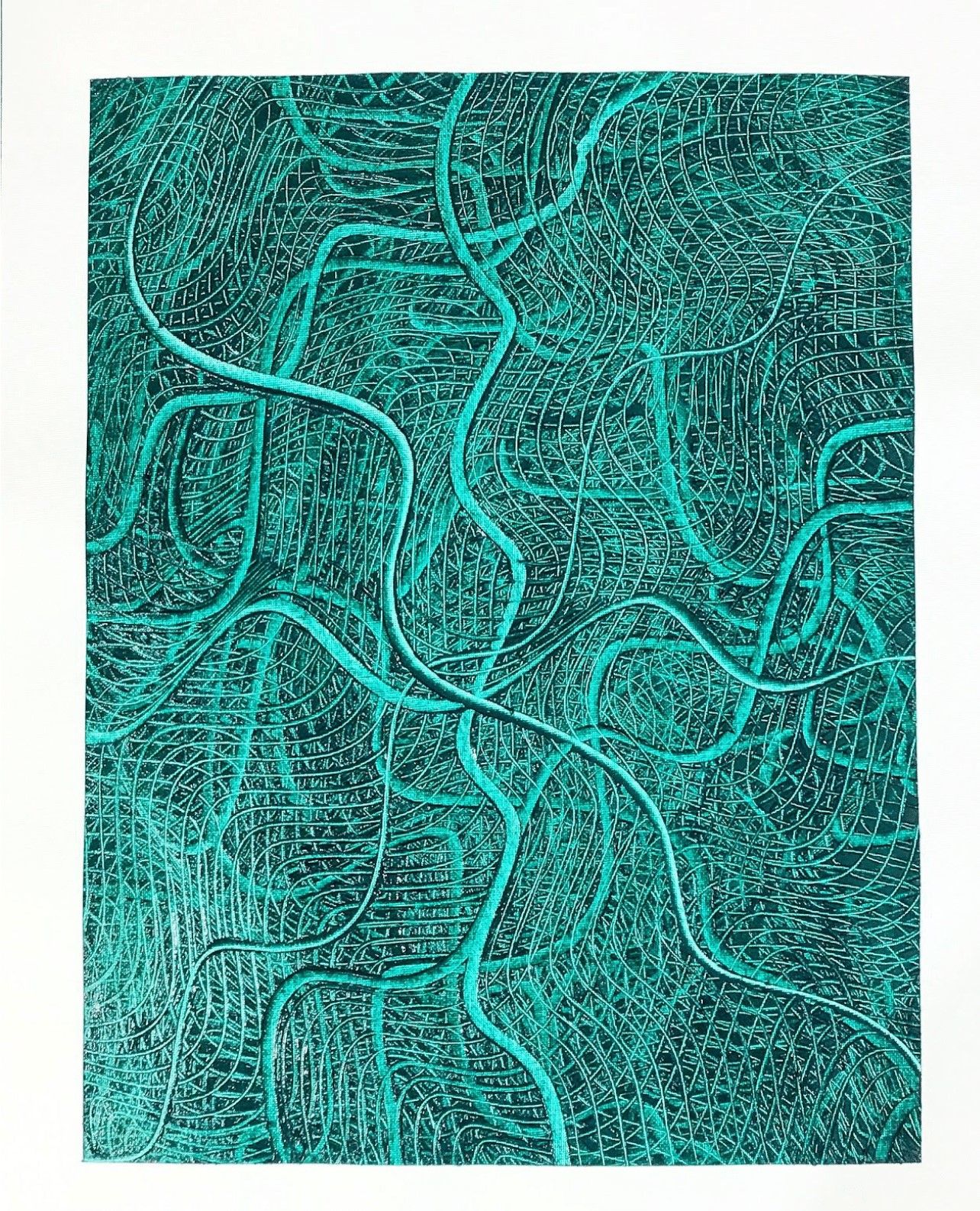

You teach me about trees:

how they exchange nitrogen

among root networks,

nourishing one another.

How when danger pierces bark,

chemicals communicate hostility,

floating through the air as if

a smoke signal became pheromones.

How the sturdiest Sitka spruces

stand tall amongst forest fires

and remain alive.

We can do more than simply remain

You tell me. You reach a hand to me

and with gracious gritty grip

pull me along. You take me

to the beach and make me cake.

You tell me this storm is in all of us,

but we can take shelter

in each other.

So we build a home

in a gale-less storm

on this obsidian

edge of time.

We fashion a hull of

thick steel and a Sitka

spruce mast. People

are windless, but You puff

our canvas sails with Your stormed lungs.

We puzzle over 5000 pieces of

I love you

into a painting of a family

with a dog who’s too cute.

Together, we do more

than simply remain

in the space You created for

our home among the storm.