Poetry

Crabs and Pines

When we moved here, the crab

tree flowered like a sculpted ball

on a stick, and the contorted pine

seemed straight out of Horton-ville.

We have pruners; we don’t use

them much. Fourteen years,

and the crab pokes at the sun

porch roof, autumn star clematis

winds through her branches,

the contorted pine bends

his back, thrusts his arms into the crab

canopy, peering through the foliage

like a professor, searching for tree

frogs who begin chirping at dusk.

Call to Dinner

The woman’s body moves

through the kitchen,

calls others wordlessly to dinner,

like the boy daydreaming by the brown pond,

with dusk coming on,

examining a tiny leaf

as if he’s grasping the whole tree,

and the little girl running

through the field

before darkness snatches the ground out

from under her

and the older boy

rubbing the fine long head

of his mule,

his face full of farm smudges

and the farmer himself,

dragging his body home

like an old wagon,

while the boy makes

a sudden grab for a frog

with his net

and the girl bursts through the gate

as the older boy considers

all that will be his some day

though at night, he knows.

it belongs to the moon and stars

and she stares out the window

at her flock coming together

in the last cringe of daylight,

praying one doesn’t bring a frog home

and a second doesn’t fall

and bruise her knee

and a third is sure that the life

laid out for him

is really the one he wants

and a fourth

who knows nothing but the land,

who may as well have been

found one day in its rich, vital soil

like Moses in the bulrushes

than born in some hospital,

who’s seldom seen

without some implement in his hand

or in the saddle of a tractor,

for this is her canvas

and she has nothing else to compare it to,

and yet, in the sinking sun,

it still rivets her attention,

in her weathered heart,

it bears up all needs,

and her mind, that soundless bell

tolls this family back to her,

in these relentless darker shades of day.

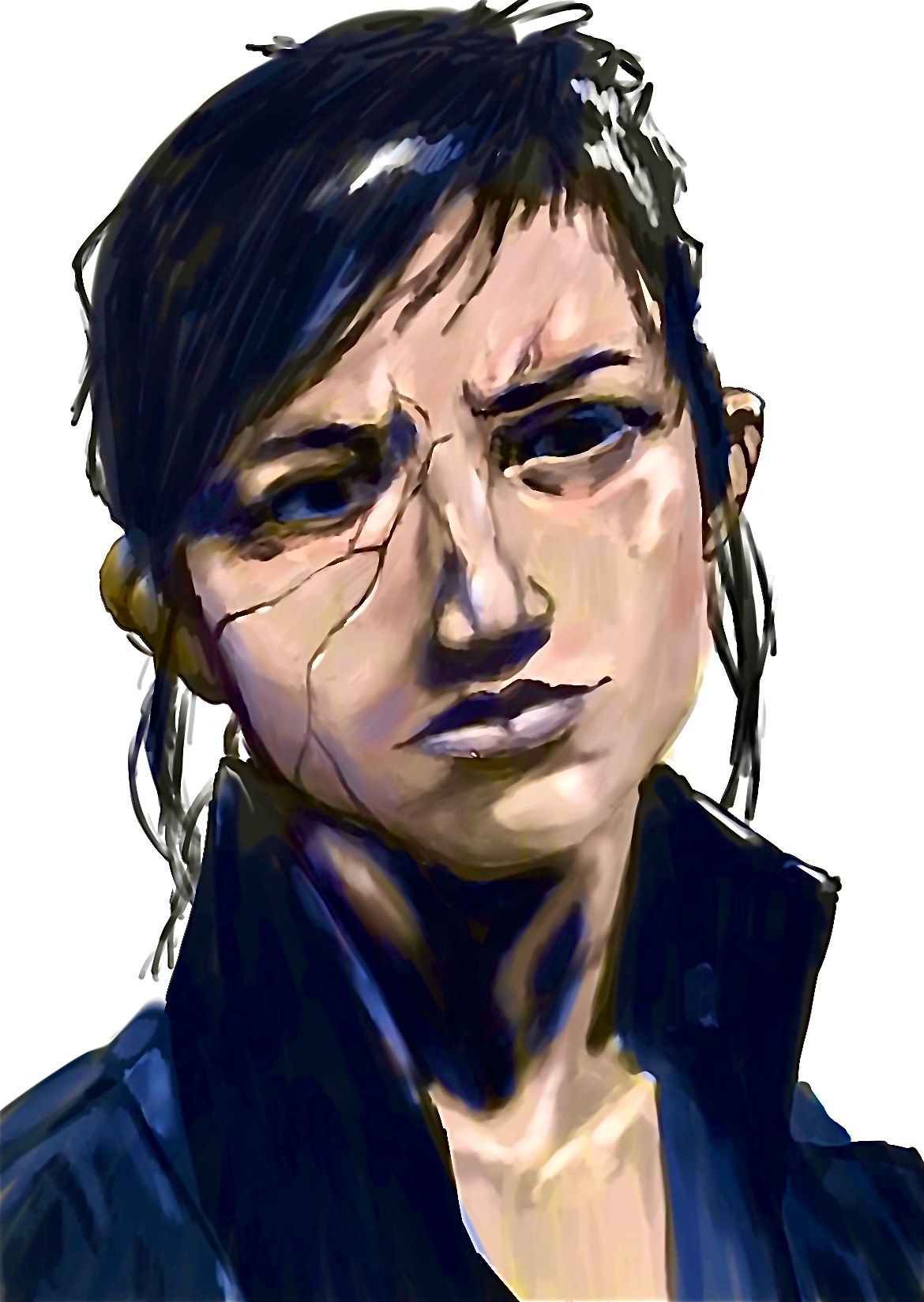

Daughter of Slovakia

She wore a bright

blue apron and

faded red

handkerchief

in her hair.

She fed the chickens

on a dusty field

outside Bratislava.

As the hot sun

beat down upon

her, she wiped

her brow.

She walked to the

village every day to

buy a fresh loaf

of bread to feed

her family.

In the evening, she

drank plum brandy

and danced to

jubilant folk

music with her

husband.

The lines around

her eyes creased

when she smiled.

She laughed a

hearty laugh.

Her eyes twinkled

with mischief and

with unspoken

dreams.

Faith in Flying

These unusual days, people driving or walking or talking are grating

my nerves: tiny brittle petals of me, littered. Pink. At home, I crochet

these bits into a shapeless sweater. But it’s not smooth. It’s seedy.

Nothing lays flat. I put on my wings, instead, hedged

by the cliffs around me. Flying is a trick

we can all learn. Take a deep breath, let go

enough so the tips of your toes dance on air.

Fly past me. Fly past you. We can all fly, Fran says,

when we don’t think about what we are doing. Do you

believe her? Does it matter? It’s the soaring that counts, the way

what we cling to flutters behind us creating kaleidoscope messages.

Furnishings

Sheepish bloat of a furniture store at night, items

faintly illumined through

the glass displaying the square footage it takes

to suggest arrangements

we can make in our pleasantly enclosed lives.

Starfish of ceiling fans, thrones

of headboards, wooden dining tables holding forth

for flocks of prim parsons chairs.

And this vehicle a vestibule for the body,

a house for aching

bones, a chamber for whatever nimble soul

may be a part of the deal.

In an airy, ancient apartment in Boston

I’ve lain with a girl I knew

I wouldn’t stay with, have seen how much

that silence can say.

The room was lovely, too. Plush king bed, gray

linen comforter, a surplus

of natural light, sensual postmodern canvases,

a sculpture of a tree in the corner.

I am still wandering streetlight-stained highways

while a furnished home beckons,

am still exhuming and examining the past,

listless, listening.